Horseboys: Irish Lackeys, Irish Footmanship—Part 2

- Wilde Irishe

- Mar 28, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 13, 2020

Footmanship

Laurent Vital visited Ireland in 1518, reporting “I have seen some of these savages, as quick in the fields, one might say, as horses.” Holinshed says of the kern at the siege of Boulogne in 1544 “being light of foot, they would range twenty or thirty miles into the country, spoiling and burning wherever they went.” On his way to Kinsale, O’Donnell in December 1601 avoided an intercepting English force by stealing a night march across a mountain which “without any rest, was above two and thirty Irish miles, the greatest march with carriage (whereof he left much upon the way) that hath beene heard of.”

J. O. Bartley (in Teague, Shenkin and Sawney) noted the playwrights of Shakespear's England made special notice of the “swiftness of foot and endurance which particularly fitted the Irish for running footmen. In Shirley's Hyde Park (1632) a race between an English and an Irish footman crosses the stage amid cries of “A Teague! A Teague! Well run, Irish!” Termock in Hey for Honesty “runs for te credit of his heels.” The footmen in Johnson’s Irish Masque “vil runne t’rough fire, and vater for tee, over te bog, and te Bannoke . . .” and in Every Man His Humour (1598) “our nimble-spirited Catso’s . . . will run over a bog like your wild Irish; no sooner started, but they’le leap from one thing to another.”

The “footmanship” of the Irish remained proverbial into the 17th century. The Irish Brigade of Alasdair MacColla serving under Montrose in Scotland in the winter of 1644/45 made a famous march over the supposedly impregnable passes of the Grampian Mountains, ravaging the Campbell’s lands. A German broadside of 1632 describes the “Ihrlander” serving in the Swedish army thusly: “They hurry over land and ice, where they go 30 miles in a day, the Irishmen running over a morass without caving in.” But by 1672, William Petty (Political Anatomy, c.vi.) said “that the footmanship for which the Irish forty years ago were very famous is now quite lost among them.” Yet Eamonn Coghlan, runner and Olympic champion, would echo these strengths of his ancestors in the 20th century!

This footmanship was a trait shared by the kindred Highland Scots, as Neal Matheson explained in his excellent ceatharine blog in 2013. Most notably, during the march to, and retreat from, Darby during the ’45 Rebellion, the Highlanders ran circles around the Government forces. In 1736, a traveler in the Highlands named Mildmay was provided with an armed escort of five men by Lord Lovat, running fully armed in their plaids. They kept pace with the six-horse coach all the way from Fort Agustus to Creiff in three days. Matheson reckons this would have been about 39 miles a day, or 3.9 mph in a 10 hour day without breaks. Mildmay’s comments sound like 16th century descriptions of the Gaelic Irish: “any of our people would think this hard duty, & hardly be able to compass it, but these highlanders do it with great ease, & when they are dry don’t want to swig down great draughts of ale or strong beer, but will take off their bonnets & dip up a little water at a spring and run on with great spirits. They are Strong, well looking Handsome people . . . very nimble & can walk or run, faster & farther, than any people whatever, and being inured to hardship in their infancys, can live harder & bear more fatigue.”

Horseboys as Faithfull Servants to English Masters

In Feb. 1581, Sir Walter Ralegh had a near escape from the Seneschal of Barrie’s Country (Imokilly) while on his way to Cork. Ralegh had a few kern, and four shot-on-horseback, and had “set on horsbacke two Irishe footmen.” Arriving at a ford ahead of his six strung-out horsemen, Ralegh was set upon by the Seneschal. Henry Moile, one of his two mounted “Irishe footmen,” had his horse founder in the ford, throwing him off. Ralegh returned to his assistance, and Moile leapt back onto his horse with such vehemence that he passed clean over the animal and landed in the mire. The horse ran off, but Ralegh sat his own horse with staff and pistol till the remainder came up.

Ralph or “Raff” Lane, lately come from mopping up the Desmond Rebellion in Munster, brought his “Irish boy” with him to Sir Walter Ralegh’s Roanoke settlement in 1585. Capt. John Smith’s History of Virginia describes Lane summoning the hostile chief Pemissapan, who “Himself being shot through with a pistol fell down as dead, but presently started up and ran away from them all, till an Irish boy shot him over the buttocks, where they took him and cut off his head.” Lane himself wrote that Pemissapan was “shot thwart the buttocks by mine Irish boy with petronell.” Ralph Lane would return to Ireland in 1586, and was serving there as Muster Master at the outbreak of Tyrone’s Rebellion in the early 1590’s.

Perrot’s Chronicle of Ireland, describes the battle of the Yellow Ford, August 1598, where Col. Percy’s regiment had the vanguard. Percy “having a foreplate or breastplate for his armour of proof with cross stings or buckles, he was shot on the breastplate there, which stunned and struck him into the mud. So, not being able to get thence without aid, his horse-boy, an Irishman, took him up, led and conveyed him away,”

Galloglass and Kern’s Servants

Nowell writing c. 1500 says of the galloglass, “every one whereof hath his knave to bear his harness whereof sume have spears, some have bowes.” And St. Leger (Salinger) in 1543 says “and for the more part their boys bear for them three darts apiece, which darts they throw ere they come to the hand strife.” A Tudor report of 1534 says “ten score spars amounteth to 20 score men,” indicating one servant. Likewise, the crown galloglass—the MacDonells of Leinster—were also only permitted a single boy, but Dymmok in 1600 says “reckoning to him a man for his harness bearer, and a boy to carry his provision, he is named ‘a spare’ of his weapon so called.” Stanihurst (in Holinshed’s 1577 Chronicle) says only that each galloglass had “a number of boys and kern” whose duty was “to spoil and kill all such as be overthrown and hurt in the fields.”

The sixteenth-century Mirror for Magistrates has the line: “The lord, the boy, the Galloglass, the kern/Yield or not yield, whom so they take they slay,” which is countered by many instances of prisoners being taken by the Irish and exchanged or paroled. However, O’Clery’s Life of Hugh Roe O’Donnell does tend to confirm Stanihurst’s note on the servant’s battlefield duties given in the previous paragraph, O’Clery saying that at the Yellow Ford, “the recruits and calones (ngiollanraid) of the Irish army returned to strip the slain, and to behead those who lay severely wounded on the field.”

Of the kern, Nowell says “every two have a ladd to bear their geare,” the Lord Justice later elaborating to Henry VIII in 1544, “in this realm every two kern have a page or boy, which commonly is nevertheless a man, to bear their mantles, weapons, and victuals.”

Irish Lackeys and Footmen in England

J. O. Bartley’s excellent study of the Stage Irishman, 1587-1659 (in Teague, Shenkin and Sawney) focuses on the figure of the Irish footman in English drama. Like the turbaned Indian footmen of Victorian England, the Irish lackey served as tangible evidence of the English conquest. Their duties were to run alongside their master’s horse and go on errands. Ostensibly set in Milan, Dekker’s Honest Whore, Part II (1604) is redolent of London and features “Bryan the Footeman” who enters and is asked if his Lord is ready— he answers “No so crees sa mee, my Lady will have some little Tyng in her pelly first,” to the exclamation “An Irishman in Italy! that so strange! why, the nation haue running heads. Then, Sir, haue you many of them (like this fellow, especially those of his haire) Footmen to Noblemen and others, and the Knaues are very faithfull where they loue, by my faith very proper men many of them, and as actiue as the cloudes,”

Bartley notes that Irish footmen in England made a special impression: “Their association with the people of position who employed them made them convenient for dramatic purposes. Their appearance, too, drew attention, for they seem to have worn their native dress as a sort of livery.” MacShane, having murdered his master in Sir John Oldcastle (1599), leaves behind “a lowsie mantle and a pair of brogs,” as well as his “strouces” (trews). Nathan Field’s Amends for Ladies (1611), one of the plays based on the notorious transvestite ‘Roaring Girl’ Mary Firth, features as a character ‘the Maid’ who disguises herself “like an Irish foot-boy”—“the prettiest boy that e’re ran by a horse.” She carries a dart.

Brathwayte’s Curtain Drawn (1621) gives the following description, and is the only period text that describes checked trews (“Guarded like two Pie collor’d Butterflies”).

“. . . I see two Irish lackyes stand

With eyther one a horse rod in his hand,

Wherewith they oft times make the Beggars to feele

The lash, for following their Lords Coach wheele.

Close be their Breeches made unto their thighs

Guarded like two Pie collor’d Butterflies;

So as to see the Jack-a-Lents come after

Would make a man half dead, burst out with laughter.”

The Jack-a-Lent reference is to the straw effigy burned in England on the first day of Lent, the inference being that the “lackeys” hair is straw-like. Bartley says: “For the footmen kept their ‘glibbes’ as well as their trowses. . . in the Welsh Embassador (1623) Antonio, in Irish disguise, is called ‘sirrah thatch’d head’ and there is a reference to his ‘Jack-a-Lent hair’.” He concludes, “From all this it seems quite certain that the Irish footmen were usually transplanted to England as they stood, and there continued to wear their native dress, retained their shaggy hair, and carried, if not always the dart, at least the less lethal horse-rod. It is also evident that this was how they appeared on the stage.”

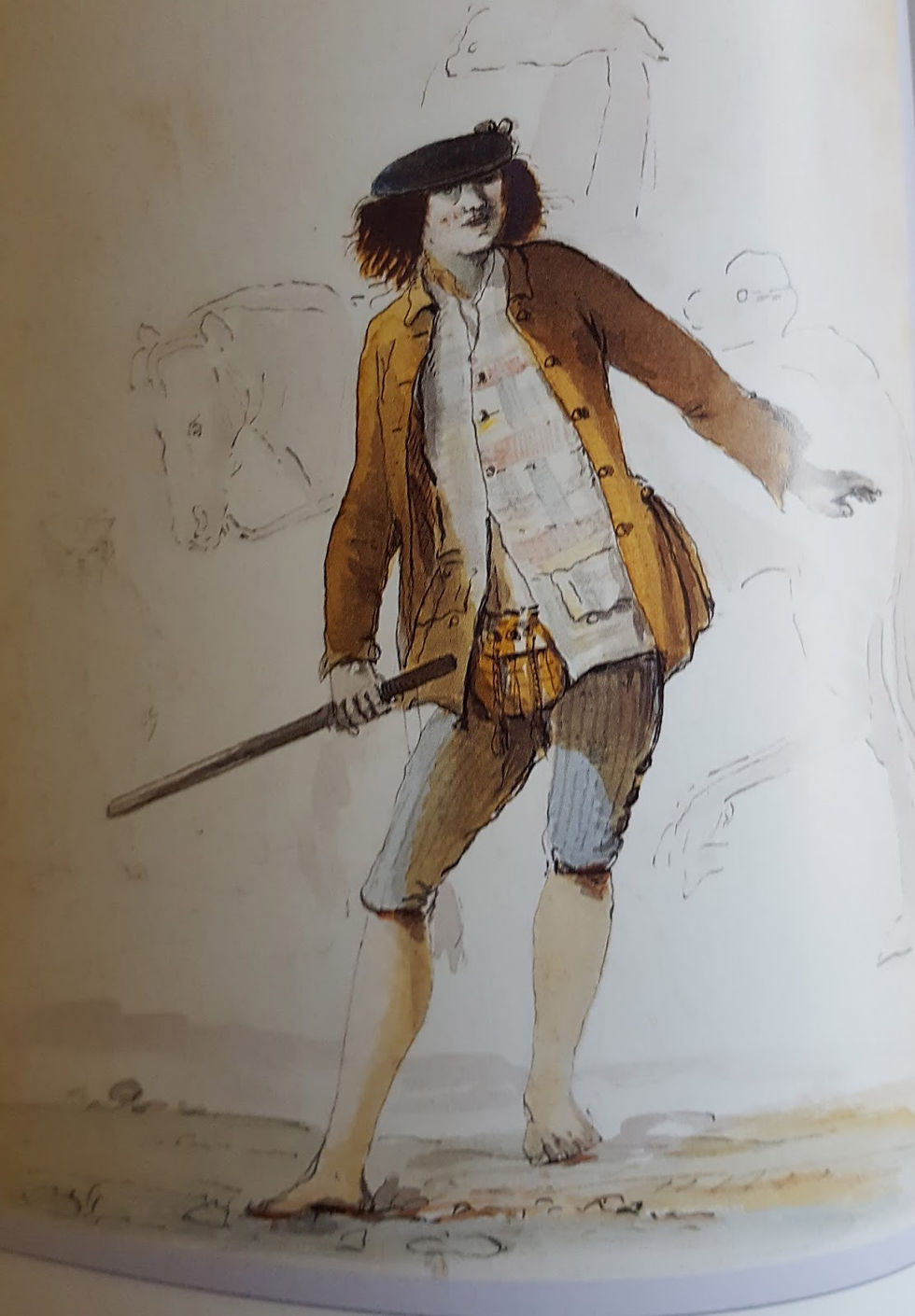

The Irish lackey from Tielch's travel album pictured above (which was probably purchased

ready-made in London), recalls ‘sirrah thatch’d head’ and the line “every Irishman with a dart lookes like death only death has not so much hair ons head,” both from The Welsh Embassador (1623). Death was often represented as a skeleton holding a barbed, feathered dart (left), as in Rowland’s Look to it for I’le Stabbe ye (1604) in which Death's Challenge has him say “But at the Irish Dart I onely deal.”

You have a sonne

Rebellious, wild, ingratefull, poore, yet

Apollo from’s owne head cuts golden locks

To have them grow on his: his harp is his,

The darts he shoots are his: the winged messenger

That runnes on all the errands of the gods

Teaches him swiftness; hee’l outstrip the windes,

—Dekker's Whore of Babylon (1607)

Next: Gaelic Domestics; An Irish Chief's Household

Comments